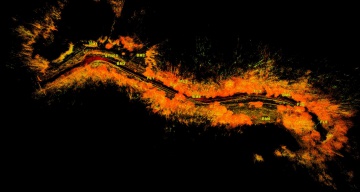

Case study:River Irwell Restoration Project

Project overview

| Status | In progress |

|---|---|

| Project web site | |

| Themes | Flood risk management, Habitat and biodiversity, Hydromorphology, Social benefits, Urban |

| Country | England |

| Main contact forename | Oliver |

| Main contact surname | Southgate |

| Main contact user ID | |

| Contact organisation | Environment Agency |

| Contact organisation web site | |

| Partner organisations | Groundwork, Natural England |

| This is a parent project encompassing the following projects |

Castle Irwell Urban Wetland, Clayton Vale, Goshen Weir removal project, River Roch, Bury, Philips Park |

Project summary

The River Irwell Restoration Project plans to restore urban watercourses in an effort to achieve good ecological status for the watercourse. Such plans must be viewed against the considerable economic and physical constraints imposed on such rivers due to their setting, in particular the need to maintain or even enhance flood protection levels and to ensure infrastructure remains uncompromised. A restoration plan was developed for the heavily modified River Medlock at Clayton Vale and Philips Park, Manchester. The principal aims of the study were driven by opportunities to improve the hydromorphological and ecological status of the watercourse through naturalisation, working to develop a watercourse where the reinstated channel units function to temporarily store coarse sediment creating dynamic habitat within a restricted urban environment.

Known as the ‘Red River’ due to the brick lining along the study reach constructed in 1912, the present U-shaped 'flume' has created conditions with limited in-channel morphology (occasional berm top fine sediments) and flow diversity (a monotonous run due to the almost uniform width and depth along the reach). No significant sediment storage occurs, despite a strong coarse sediment supply, as a consequence of the unchanging steep gradient and immovable planform (the brick-lined banks have restricted any lateral movement of the watercourse locally) creating a uniform, high energy, transporting reach and preventing any sediment deposition on the channel bed. Under present flow conditions, the high velocities are considered to be a barrier to fish passage, due to velocities of >2m/s under low flow conditions and 3-4m/s during higher flow events within the channel.

The River Medlock at Clayton Vale and Philips Park is designated as a Heavily Modified Waterbody. At present the Water Framework Directive (WFD) defines the overall river status as Poor Ecological Potential, but with a target of reaching Good Ecological Potential by 2027. Restoration needed to be mindful of impacts locally, and upstream and downstream of Clayton Vale and Philips Park, including impacts on flood risk given the highly urbanised nature of the catchment. Removing the brick-lining and concrete base layer, without managing the steep gradient and high energy levels of the River Medlock could create uncontrolled destabilisation. Therefore, removal had be considered alongside morphological restoration and naturalisation through Clayton Vale and Philips Park to ensure a 'dynamically stable' restoration was implemented and that historic features lining the watercourse were not compromised.

Consultation throughout the restoration plan development highlighted the ‘stand-off’ between the objective of river naturalisation and the ‘need’ for stability. The River Medlock at Clayton Vale and Philips Park would be a dynamic, active single thread river if not constrained by the brick – lining flume. Upstream analogue features (including, rapids, riffles and pools) and hydraulic modelling were used to carefully design and size functional, dynamically ‘stable’ morphological features to manage the high energy system following removal of the concrete and brick lining. Engineering concerns remained over the potential for ongoing lateral erosion that could threaten local historic walls and public footpaths. Compromise was therefore necessary to satisfy the project board before works could be undertaken, however, the majority of the restoration objectives for naturalisation were approved and the results of the first stage of the project and initial river response is reported here.

Monitoring surveys and results

The project will be monitored.

Lessons learnt

Utilise the material within the channel where possible to reduce the costs and impacts of importing foreign material.

Image gallery

|

Catchment and subcatchmentSelect a catchment/subcatchment

Catchment

Subcatchment

Other case studies in this subcatchment: Clayton Vale, Philips Park

Site

Project background

Cost for project phases

Reasons for river restoration

Measures

MonitoringHydromorphological quality elements

Biological quality elements

Physico-chemical quality elements

Any other monitoring, e.g. social, economic

Monitoring documents

Additional documents and videos

Additional links and referencesSupplementary InformationEdit Supplementary Information The River Irwell rises at Deerplay Moor, Cliviger (Lancashire) and runs south through Bacup, Rawtenstall, Ramsbottom, Bury and Kearsley before joining the Manchester Ship Canal in Salford, south of Irlam. Major tributaries include the Roch, the Croal, the Irk and the Medlock. This phase of the RRC‟s work (Phase 1) concentrated on the Irwell between Rawtenstall and Salford, and the Kirklees Brook between Hawkshaw and its confluence with the Irwell. The Croal and the Roch will be the subject of a similar study in the future (Phases 2 and 3). The upper region is largely rural and fairly steep whereas the lower region is mostly urban and less steep. More than 30% of the catchment is urban including Manchester, Salford and Oldham in the south and Bury, Bolton and Rochdale in the centre (Environment Agency, 2008). The river has a long history of modification dating back to the industrial revolution, which includes walling, deepening, re-alignment, culverting, widening, dredging, straightening, and the construction of weirs. Many of these structures are now in poor condition and are crumbling or collapsing into the river channel, contributing to the supply of coarse, but unnatural, bedload material. Artificial structures such as weirs and culverts can also obstruct flow and result in accumulations of sediment within the channel, which in the past has been removed by channel dredging at some locations. Many of these structures were constructed as part of historical industrialisation of the area, and where they have collapsed there is evidence that the river has begun to naturally adjust, often with riffle features occurring downstream. In most cases there was little or no evidence (from the walkover survey) of any negative impacts in terms of additional fine sediment accumulation downstream.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||